Caribou- the Bringers of Life

/When most of our guests see the reindeer, they see Santa. They see Rudolph and think of holidays, time with family, and holiday magic. The reindeer give them warm, fuzzy feelings of Christmas, and while I certainly have many fond memories of family holiday gatherings, I see something entirely different when I look at the reindeer.

For me, I see the caribou. I see massive herds of majestic animals bringing life to an otherwise desolate and unforgiving, windswept land. There’s something about watching the caribou as they so effortlessly cross the tundra, that steals my breath away. That brings tears to my eyes. Caribou are the bringers of life. Where caribou tread, life follows. Wolves, fox, ravens, wolverines, bears, mosquitos, birds, humans- where there are caribou, you will find other life. And even though I know that to be the case, it still catches me off guard. I’ll look out across a landscape, apparently devoid of life, and think- what can survive in this harsh environment? I feel exposed without trees to provide warmth and shelter. I think about how easily I would die if I didn’t have my Arctic Oven tent with Duralogs for heat and prepackaged meals. How easily I’d die without my parka and boots and team of dogs (or skis or plane or whatever brought me to this remote spot). And then from a far off hill, you see them coming. They look to be strolling, as if meandering through a garden, yet I know that their stroll is even faster than my speediest sprint (which I guess isn’t actually saying much, but you get the idea). And as they pass through the valley or drainage, other life appears. Sometimes I’m not fortunate enough to see it with my own eyes, I’ll only see the other life in the form of tracks or poop, but sometimes, I get to watch the wolf trot across hillside. The fox scamper beneath the willows. Caribou are majestic and regal, yet also so goofy. At times, I get the impression that no one knows where they’re going. I envision someone from the back of the herd going- who’s driving this bus? I’ll see videos of caribou standing on an ice floe in the Yukon during breakup. Caribou are these beautiful creatures of purpose and drive mixed with spontaneity and improvisation.

One of my core memories was from a hunt a couple years ago. I watched a large group descend a hillside and angle to cross a frozen river. I sprinted to a hiding spot in the cut bank and waited. I waited and waited, not quite sure where the herd would decide to cross. What luck- they crossed not 30 yards from my hiding spot on the cut bank. They bottle-necked into a single line and trotted across the glare ice of the frozen river. Well, some trotted. Others would slip and slide, spider-webbing onto their bellies as they (pardon my language) literally ate shit in front of me. Or as Tucker would say- biffed it. It took all my self control not to audibly laugh. The entire group ended up being cows and calves, so no meat from that bunch, but I found myself feeling so fortunate to have been sitting on that cut bank at that moment.

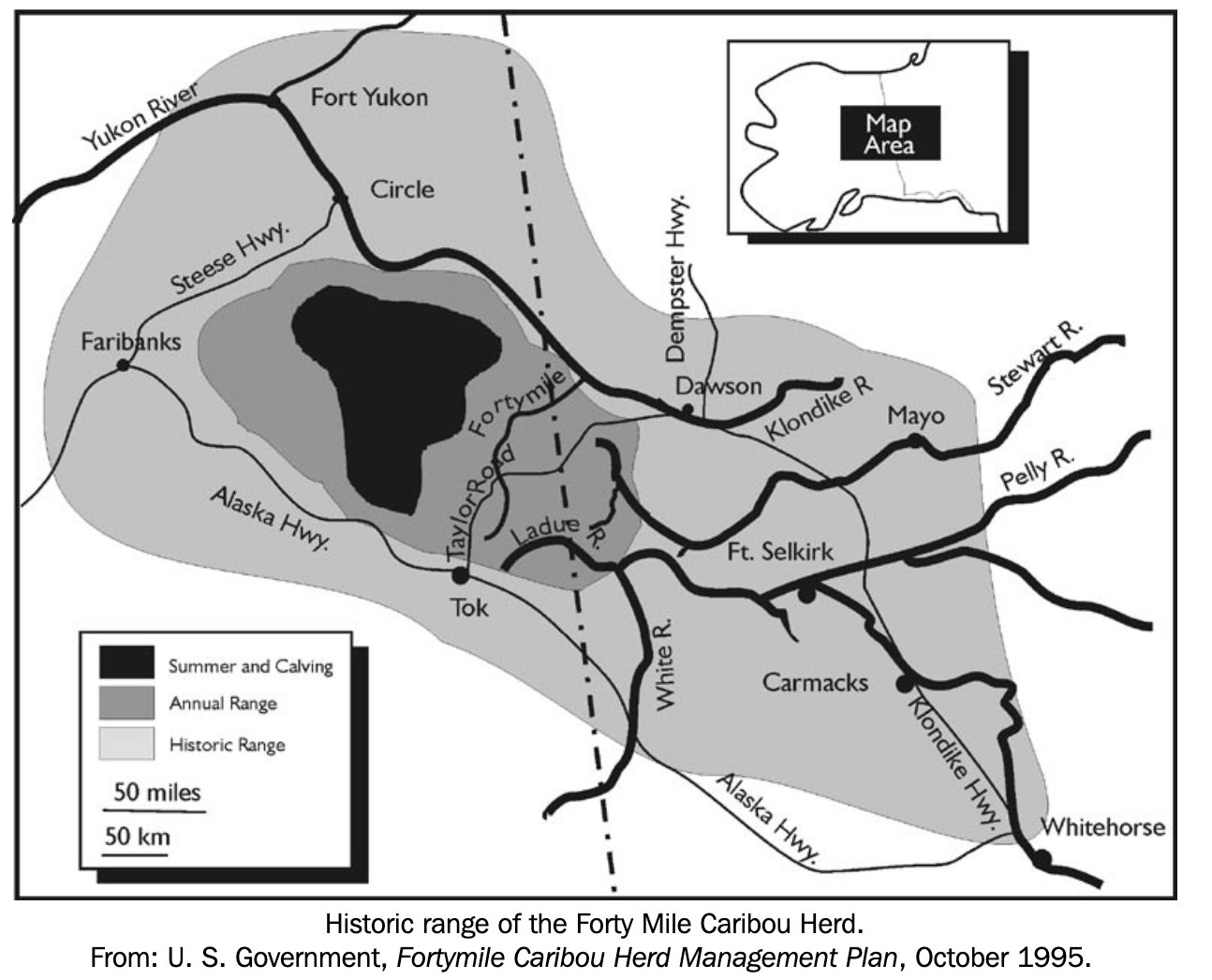

It is due to my love of caribou and everything they encompass that I find myself fearing for the future of the Arctic. And I know, I know, there’s enough stuff to be worried about these days, but this is worth talking about. The Arctic is changing. I made a post last year around this time about the disappearing salmon, particularly in the Yukon (numbers are still abysmal by the way). And as the salmon bring life to the waterways, the caribou bring life to the tundra. And there has been cause for concern. Now, before I go too doomsday, caribou are also known for their success stories. These animals can come from behind and with the right conditions, they can rebound. Take the Fortymile herd for example. The below chart shows their rebound from about 5,000 animals in the 1970s to 73,000 in 2017.

However, back to my more doomsday attitude, recent counts in 2022 are down to 40,000 animals, and the herd is on the decline. The overall nutritional status of the herd has been declining, and they have been overgrazing their range. Interestingly, their range has also shrunk drastically. Oftentimes, a herd’s range shrinks as the population shrinks, but the question is, will it return to it’s former size? Will future generations of caribou know where to migrate and travel? If a caribou scientist is reading this and knows the answer, please comment! Another peculiar thing to note- the current harvest plan for the Fortymile winter hunt allows the harvesting of cows. My uneducated assumption is that cows are instrumental in population growth. If that’s the case, why would harvesting cows be best for herd management? Even if their nutritional status is declining and they’d die from starvation, wouldn’t that motivate the herd to expand it’s range searching for additional food sources? Again, I’m not educated in biology, so take these speculations with a grain of salt. And if you’re a caribou scientist, again, I’d love to hear your opinion!

Moving on from the Fortymile herd and its decline, let’s look at the Northwest Arctic Herd. This is one of the largest herds in the world, and it too has been declining for the last five years. Current counts have the herd at 164,000 animals, an almost 13% decrease from last year. Herd population estimates have been dropping from 259,000 in 2017 to 244,000 in 2019 and 188,000 in 2021. Additionally, the herd has been changing its migration patterns. They’ve been migrating TWO MONTHS later than usual from their summering grounds. Typically, they migrate from their summering grounds on the North Slope and cross the Kobuk River to the Seward Peninsula. In the last couple years, some animals aren’t even making it to the Seward Peninsula and are instead ending up in the Brooks Range. Wildlife biologist Kyle Joly says, “Those movements are largely driven by snowfall and cold temperatures. They’re making those decisions based on changing climate.” He goes on to say, “the thing that stands out the most is that we’ve had a low survival rate of adult females, adult cows. What’s causing the decline or lower survival rates of cows, we just don’t know. We are looking into different factors.” Biologists speculate reasons may include changing migration patterns, increase wolf predation, and climate warming affecting food sources.

With larger factors like climate warming being more challenging to alter, this brings me to the last topic I wanted to discuss: resource development in the Arctic and specifically the Ambler Road. I understand the importance of resource development. I personally benefit every year with a lovely little permanent dividend fund check being deposited into my account. This last fall it totaled $3284 per Alaskan resident. Beyond that, I understand that resource development provides jobs and income to the state. However, I’m also a firm believer in balance and responsible resource development. There is currently a project being slowly pushed through called the Ambler Road. Totaling 211 miles, the Ambler Road would be a private industrial access road to the Ambler Mining District. The Ambler Road would cross through the Gates of the Arctic National Park (sidenote- it would bring noise to the quietest recorded landscape in the entire National Park Service- Walker Lake) and potentially disrupt caribou migrations (among other things). Remember how I keep harping on caribou being the bringers of life and a foundational animal in the Arctic ecosystems? I’ve heard supporters of the road say that the caribou can just cross the road. It won’t affect them. They walk all around the pipeline.

There was a decade-long study that looked at caribou and whether they crossed the 53-mile Red Dog mine road during their fall migration. It found that about a quarter of the caribou balked at crossing the road, the slowest of whom took 10 times as many days to get across as “normal crossers.” A handful never crossed the road at all and wintered in a completely different area. Those that crossed the slowest walked an average of 300 km more in their fall migration than the caribou that crossed the road. Caribou biologist Jim Dau said, “once they got to the south side of the road, they traveled 60 percent faster than the animals that crossed without delay. To catch up to the caribou that crossed earlier, the slow crossers put on the afterburners. What used to take them two to three weeks to go through an area -- they can do that in two or three days.” What does that mean for the food in the area? For the overall health of the caribou?

If so many caribou were affected by a 53-mile road in a corner of their range, what would a 211-mile road do? Many of the surrounding communities also oppose the Ambler Road as it will directly threaten their way of life. Not to mention, many of the herds are already feeling stress and populations are decreasing from the warming climate. Ultimately, I’ll leave everyone with this- a photo taken by Kristin Knight Pace as she flew over the landscape that could eventually be crossed by an industrial road. Life is a balance. Economic growth and resource development are needed for our state, but so is protection of our wildlands. And with those wildlands, caribou form the backbone. The bringers of life.

I’ll note, this is my personal blog. Please question the facts and do your own research. I’m not a biologist nor do I claim to know the answers. Caribou and the Arctic are something I feel passionately about, and I hope that future generations can experience the joy of wildness as I have.

If you feel strongly about the Ambler Road and would like to contribute to the No Ambler Road Coalition, any donations made between now and November 29th will be matched up to $15,000!